IowaCulture.gov

In 1900, something special started to grow in Southeast Iowa and it developed into a paradise for Black Americans.

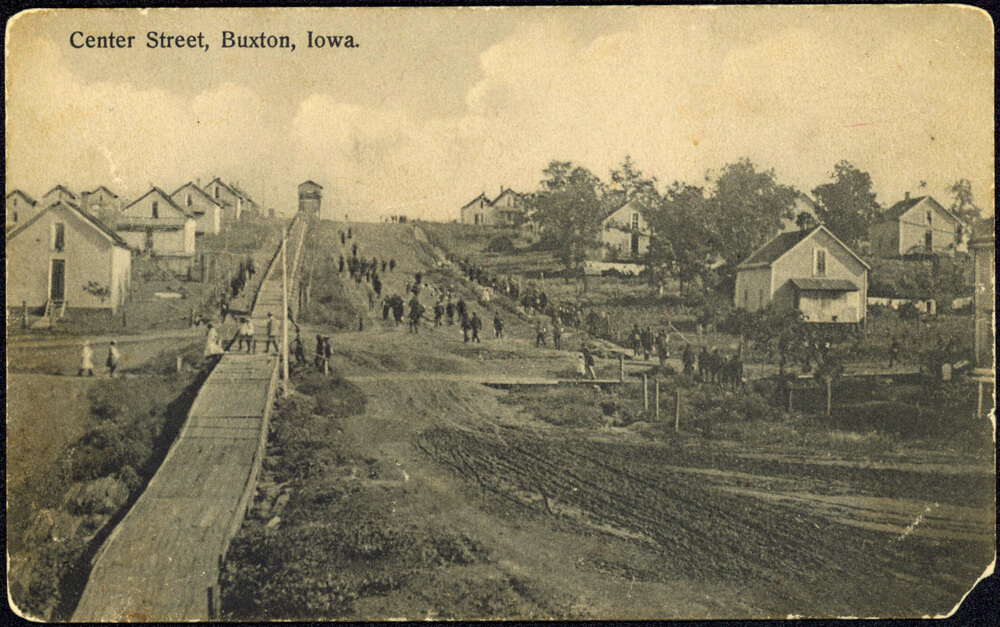

For 27 years Buxton, Iowa, served as a racial utopia where segregation was not officially or socially enforced. Black citizens had the same opportunities and standing as white residents, and a true community developed.

Black doctors treated Black and white patients. Black businesses were plentiful, schools were integrated, and interracial marriage was accepted.

The story started, as many did in the late 1800s, with miners, labor strikes, and unionization efforts.

Miners across the country demanded better pay and benefits, which touched Iowa’s mines too. Consolidation Coal Co. and Chicago & North Western Transportation Co. handled it the way many companies did: they had recruiters go to Virginia and recruit Black miners to break the strikes.

But unlike in other places, the presence of the strikebreakers in Muchakinock—the smaller pre-cursor to Buxton—did not incite violence, nor did it inspire more strikes. In fact, the company continued recruiting Black miners for work. To the point that eventually the majority of the town’s population—66%— was Black.

[inline-ad id=”1″]

As with most mining towns, Muchakinock closed as the mines produced less. Benjamin Buxton was given the reins to establish another town when he was made superintendent of the Consolidation Coal Co. Buxton was determined to make it unlike any other mining town.

He was hands-on with the development, poured significant resources into the community, and actively encouraged integration. Like many men in his position, Buxton subscribed to a philosophy known as welfare capitalism, wherein the company provided for all of the necessities and comforts of life to keep the workforce happy and prevent strikes.

Buxton had schools, housing the company maintained, several stores—not just the company store—multiple churches, a YMCA, and town favorites such as the Buxton Cornet Band and the Buxton Wonders baseball team, both all-Black. The latter two even had support from the company in the form of sometimes having their uniforms paid for.

For celebrations, fairs, and events such as Emancipation Day, the mines and most businesses were closed so people could attend. The Buxton family was so supportive it contributed food and refreshments for those celebrations.

[inline-ad id=”2″]

Black residents in Buxton had a variety of professional and authority roles including lawyers, doctors, teachers, barbers, a tailor, property owners, and entrepreneurs, among many others. Some of the businesses included hotels, grocery stores, restaurants, a bakery, drugstores, and newspapers, among others.

Any segregation that happened was by choice. For example, Swedish immigrants largely lived in suburbs mostly populated by other Swedes, and some churches were attended by only one race.

But lack of segregation wasn’t a tenet of welfare capitalism, so why did Buxton have and enforce policies which promoted equality? It made economic sense to be tolerant because of the predominantly Black workforce, but the level of support for equal opportunity was unique to Buxton.

[inline-ad id=”3″]

In “Creating the Black Utopia of Buxton, Iowa,” author Rachelle Chase—also a former Starting Line reporter—says it probably comes down to the men in charge. However, there’s no way to confirm that because no records were found to explain why they ran Buxton how they did.

For the Buxtons, there was family history connected to the Union Army during the Civil War. The McNeills, who started Buxton’s antecedent, Muchakinock, came from an antislavery family.

With those bones in place, each new architect, from the McNeills down to Ben Buxton, built upon previous success.

However, Buxton’s fate traveled the same road Muchakinock did. Mines were closed as they dried up, so workers left to find work elsewhere. The mining company relocated to other towns as it had before. Ben Buxton went back home to Vermont and the family farm in 1915.

[inline-ad id=”4″]

Some residents moved to the new settlements—Consul, Bucknell, and Haydock—but fewer social opportunities and the dwindling original population meant the energy had faded. By 1919, about 400 people lived in Buxton. It was essentially a ghost town by 1922.

Haydock was set up similarly to Buxton with integration, but by 1924 Consolidation Coal Co. was no more. Also, demand for Iowa coal was declining. In 1927, a national strike happened and even the miners of Haydock participated.

Nothing ever quite recovered after that, and the fate of Haydock was also sealed.

Now, all that’s physically left of Buxton are ruins in an open field.

[inline-ad id=”5″]

But it lives on in articles and books, including Chase’s “Creating the Black Utopia of Buxton, Iowa,” and her first book, “Lost Buxton.” Also through stories told by former residents.

The Buxton Townsite is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Monroe County Historical Society and the State Historical Society of Iowa, and museums such as the African American Museum of Iowa in Cedar Rapids, have also kept Buxton alive by preserving artifacts and the town’s remains.

The original site is on privately-owned land, but owner Jim Keegel removed it from farming and set it in the Conservation Reserve Program. Visitors can arrange tours through the Monroe County Historical Society.

Interviews with original Buxton residents have been digitized by the State Historical Society of Iowa—at Chase’s urging—and the historical society has them, along with transcripts and photographs.

Further information about Buxton, as well as efforts to honor its memory, may be found at www.LostBuxton.com

Nikoel Hytrek

02/24/22

Iowa Starting Line is part of an independent news network and focuses on how state and national decisions impact Iowans’ daily lives. We rely on your financial support to keep our stories free for all to read. You can contribute to us here. Also follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

[inline-ad id=”0″]

Politics

Biden announces new action to address gun sale loopholes

The Biden administration on Thursday announced new action to crack down on the sale of firearms without background checks and prevent the illegal...

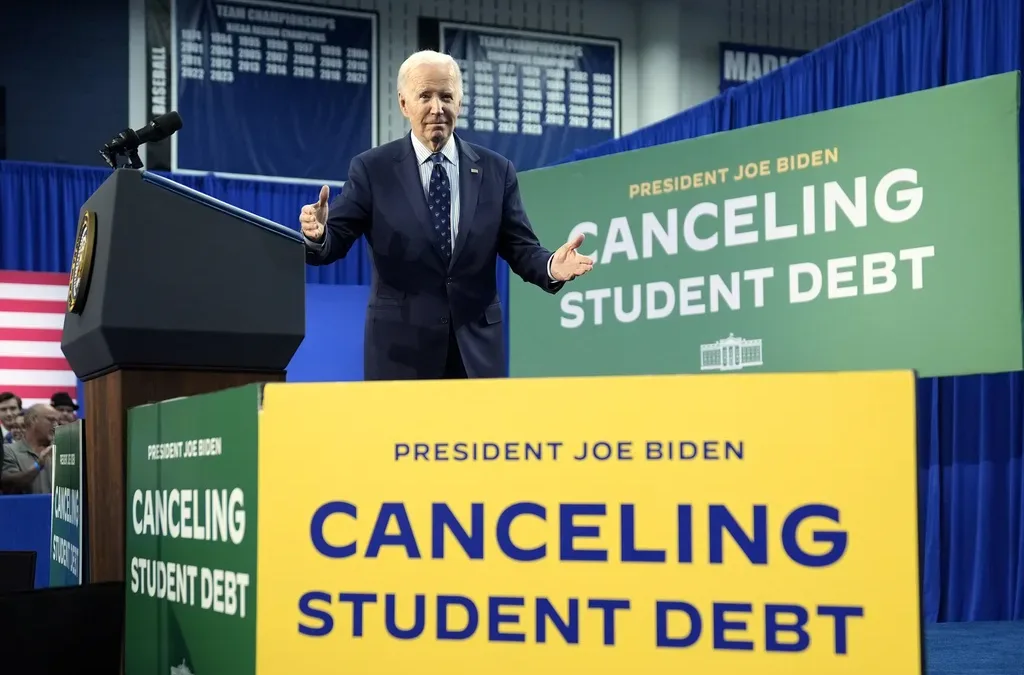

Biden cancels student loan debt for 2,690 more Iowans

The Biden administration on Friday announced its cancellation of an additional $7.4 billion in student debt for 277,000 borrowers, including 2,690...

Local News

No more Kum & Go? New owner Maverik of Utah retiring famous brand

Will Kum & Go have come and gone by next year? One new report claims that's the plan by the store's new owners. The Iowa-based convenience store...

Here’s a recap of the biggest headlines Iowa celebs made In 2023

For these famous Iowans, 2023 was a year of controversy, career highlights, and full-circle moments. Here’s how 2023 went for the following Iowans:...