In May 2014, two months after the release of Joni Ernst’s first TV ad as a candidate for U.S. Senate, the Des Moines Register Editorial Board wanted to know what Ernst’s vision for the country was when it came to going to Congress to make Washington “squeal.”

“My vision is to get us on a track of fiscal responsibility,” said Ernst, then a two-term state senator from Southwest Iowa.

“Right now we have a $17.5 trillion debt and it grows every day, so we do have to cut spending, and I would support a balanced budget amendment. I think that’s one of the first steps to getting us on the right track.”

In her famous Squeal ad, Ernst was blunt and to the point. “I’ll know how to cut pork,” she pledged.

It’s been six years since Iowans first heard Ernst’s “make ’em squeal” promise. The national debt now sits above $26 trillion. The federal government’s annual spending deficit was $984 billion in Fiscal Year 2019, the highest amount since 2012. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, the projected end-of-year deficit for Fiscal Year 2020 shot up in the spring and is expected to hit $3.7 trillion by year’s end.

In 2015, shortly after taking office, Ernst joined all of her Republican colleagues in co-sponsoring Sen. Orrin Hatch’s proposal to amend the Constitution to require the federal budget be balanced, meaning the federal government could not spend more than it collects in revenue. Two years later, Sens. Mike Lee and Chuck Grassley introduced the idea again, but it gathered no additional sponsors and did not advance out of the Judiciary Committee.

[inline-ad id=”4″]

Now in the midst of her first reelection campaign, the theme of fiscal responsibility and desire to “cut pork” are not nearly as prevalent as in 2014. This time around, Ernst’s message is more focused on the “mission to stamp out socialism,” reducing economic dependence on China, opposing Democrats’ health care plans and championing the conservative judges appointed to the Supreme Court. (Ultimately, the pandemic has taken over political campaigns in 2020 and left little room for the talking points candidates had planned to run on.)

SQUEAL Act

When asked in a recent interview to provide examples of her cost-cutting efforts, or instances where she broke with members of her party, Ernst cited her 2017 SQUEAL Act.

The bill eliminates a $3,000 tax deduction members of Congress receive for living expenses.

“We did away with that tax break and that did not make me popular with anyone of any party, but we felt it was important to do because our constituents didn’t receive those same tax breaks,” Ernst said on the podcast “Politics with Amy Walter.”

She proudly noted that the bill, impacting the 535 legislators in the House and Senate, was included in Republicans’ 2017 tax overhaul. What Ernst failed to mention is the negative impact the tax law is expected to have on deficits (the annual amount showing how much federal spending exceeded revenue). According to the Congressional Budget Office, between 2018 and 2027, the projected cumulative deficit will reach $11.7 trillion in part due to the financial ramifications of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

[inline-ad id=”1″]

Squeal Awards

Continuing with the barnyard theme, Ernst’s press team sends monthly updates on the latest “squeal award” recipient.

In July, the “government waste” and “inefficiencies” highlighted by Ernst were at the Department of Veterans Affairs. Ernst cited a report showing a 25% increase to the VA public affairs staff over the last several years and “nearly $20 million … spent on artwork to decorate VA buildings.”

In May, shortly after the House passed its latest coronavirus relief legislation, Ernst pinpointed “jobless millionaires” for the month’s squeal award. Ernst’s RICH Act bars people who are unemployed but earning $1 million or more this year from receiving the unemployment insurance provided by the federal government during the pandemic, which at the time of the bill was $600 per week. Keeping millionaires off the federal unemployment rolls could save up to $2 million per week, Ernst said.

And in February, Ernst shined a light on a $356 million Presidential Election Campaign Fund that collects taxpayer dollars to help fund presidential campaigns, even though no presidential candidate in the last 16 years has applied to use the public funds. In response, Ernst introduced the ELECT Act to eliminate the fund and redirect the money toward paying down the national debt.

[inline-ad id=”2″]

Proposed Legislation

Over the last five-and-a-half years, Ernst has introduced more than a dozen bills aimed at reducing wasteful government spending. A few have become law, but in comparison to the $4.4 trillion spent by federal agencies last year, the well-intentioned initiatives are a drop in the bucket.

The Program Management Improvement Accountability Act is a cost-cutting bill she authored that did become law. Ernst introduced the bill in June 2015 and it was signed into law Dec. 14, 2016 by President Barack Obama. The legislation establishes entities in the federal government to ensure projects are completed on time and on budget.

Program management is an issue Ernst raised during her first interview on “Iowa Press” in May 2015.

“I think we do need to have more program managers in the federal government that know lean methodology, those that really do know how to manage programs and keep costs in line, those that are watching those contracts to make sure that they’re on time and on budget,” Ernst said.

Longtime Iowa journalist Kathie Obradovich challenged Ernst in the interview to explain whether “a major percentage of spending” could be reduced by nibbling around the edges of multi-billion budgets “or do you really have to wholesale entitlements and eliminate programs?”

Ernst did not specifically address how to reduce spending on so-called entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, nor did she explain how program management initiatives would make a significant impact on federal deficits.

“Well, I think we have to take a look at what programs are in existence out there,” she said. “Like I said, if they are not working for the benefit of the American people, we need to take a second look at that. If you look at government contracting, I think that’s one area that really needs significant improvement.”

[inline-ad id=”3″]

Other examples of cost-cutting legislation include the 2019 Presidential Allowance Modernization Act, which puts limits on taxpayer-funded benefits for former presidents. The bill’s counterpart in the House passed last fall but has not been taken up by the full Senate. As Ernst often points out, she first introduced this bill in 2015. It passed the House and Senate but was vetoed by then-President Obama.

Ernst’s Billion Dollar Boondoggle Act and Bogus Bonus Ban Act became law as part of a 2019 appropriations bill. Again, the fiscal impact is small, if at all. The boondoggle bill requires the director of the Office of Management and Budget to submit to Congress an annual report on every government project that is $1 billion over budget or five years behind schedule.

The bill related to financial bonuses aims to save hundreds of millions of dollars by requiring new government contracts that include bonuses to tie the additional money to positive outcomes. As an example, Ernst cited a report from NASA stating that the space agency has paid bonuses totaling more than $500 million to contractors working toward the next manned moon mission, despite contractors’ “poor performance” that has put the project billions of dollars over budget and years behind schedule.

In an effort to save about $250,000 on custom-made costumes for government mascots, Ernst moved her SWAG Act through the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee. Citing a report from the Government Accountability Office, Ernst said federal agencies spend about $1.4 billion annually on public relations and advertising campaigns. Prohibiting the federal government from creating mascots amounts to less than one percent of the amount GAO says federal agencies spend on public relations and advertising.

[signup_form]

As a former Army officer, Ernst also has been asked how the annual budget for the Department of Defense, proposed this year at $695 billion in the House and $740 billion in the Senate, can be pared down.

“I think every department needs to be on the table, including defense, absolutely,” Ernst said during the 2014 Editorial Board interview. “Now, I’m going to stand behind a strong military force. I don’t think that down-sizing our troops to the level that’s proposed right now is a smart way to do it, but I do see there is a lot of waste in the Department of Defense, and that is across the board.”

The Washington Post reported last year that military spending fell “gradually” from 2010 to 2015 but rose again in 2016 “and has increased every year since.”

“Overall, military spending has already increased from $586 billion in 2015 to $716 billion in 2019,” the newspaper reported.

In the Fiscal Year 2021 National Defense Authorization Act passed by the Senate last month, Ernst’s COST Act is included as a way to ensure grant recipients who get money from the Pentagon disclose how much their military research is costing taxpayers.

Trump has yet to sign the defense department’s spending bill into law.

[inline-ad id=”5″]

Why Deficits Continue To Increase

By embracing the label of “the Senate’s leading foe of wasteful government spending,” Ernst has put herself in a catch-22. You would be hard-pressed to find a person in government who would not admit to inefficiencies and wasteful spending given the enormity of the budgets doled out in Washington, D.C. On the other hand, budget experts on both sides of the aisle acknowledge that “mandatory” spending — Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, certain disability and retirement benefits and unemployment insurance — is the greatest contributor to the national debt.

There are three ways to slash deficits: raise revenue, cut spending or a combination of the two. As a Republican, Ernst is unlikely to support tax increases as a way to bring more money to the federal government, so that leaves spending cuts.

A report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities show 61% of federal spending in Fiscal Year 2019 was mandatory, 30% was discretionary (national security, transportation and economic development, health care research, diplomacy, law enforcement, etc.) and 8% was interest on the national debt.

The problem for lawmakers is that cuts to Social Security and Medicare in particular are not popular with their constituents and therefore politically unpopular for them to pitch as a way of bringing down the national debt.

Ernst has experienced this backlash firsthand since suggesting lawmakers should “sit down behind closed doors” to discuss Social Security reform. That comment has since shown up in ads opposed to her reelection.

[inline-ad id=”6″]

Meanwhile, Republicans like Ernst significantly contributed to the rising deficits they rail against in Congress and on the campaign trail by passing the GOP tax bill in 2017.

The $1.5 trillion bill Ernst voted for lowers the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%, increases the standard deduction, expands the child tax credit, temporarily lowers individual tax rates and repeals the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate on health insurance. At the time, tax experts acknowledged the temporary relief the law will provide some poor and middle-class Americans (tax cuts for individuals expire after 2025), while pointing out how the long term benefits overwhelmingly favor corporations and the wealthy.

The tax law “provides by far the largest benefits to high-income people and many middle- and lower-income people would end up worse off,” according to a 2017 report from the nonpartisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

“By 2027, when many of its provisions would have expired, those at the top would still get large tax cuts, but every income group below $75,000 would face tax increases, on average,” the report states. “Yet despite raising taxes on millions of middle- and lower-income households, the bill would add $1.5 trillion to deficits over the decade due to its large tax cuts for high-income households and corporations.”

Since Ernst entered the Senate in 2015, spending deficits have increased each year:

2015: $439 billion

2016: $587 billion

2017: $665 billion

2018: $779 billion

2019: $984 billion

2020: $3.7 trillion (projected)

By Elizabeth Meyer

Posted 8/12/20

Iowa Starting Line is an independently-owned progressive news outlet devoted to providing unique, insightful coverage on Iowa news and politics. We need reader support to continue operating — please donate here. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook for more coverage.

Politics

Biden announces new action to address gun sale loopholes

The Biden administration on Thursday announced new action to crack down on the sale of firearms without background checks and prevent the illegal...

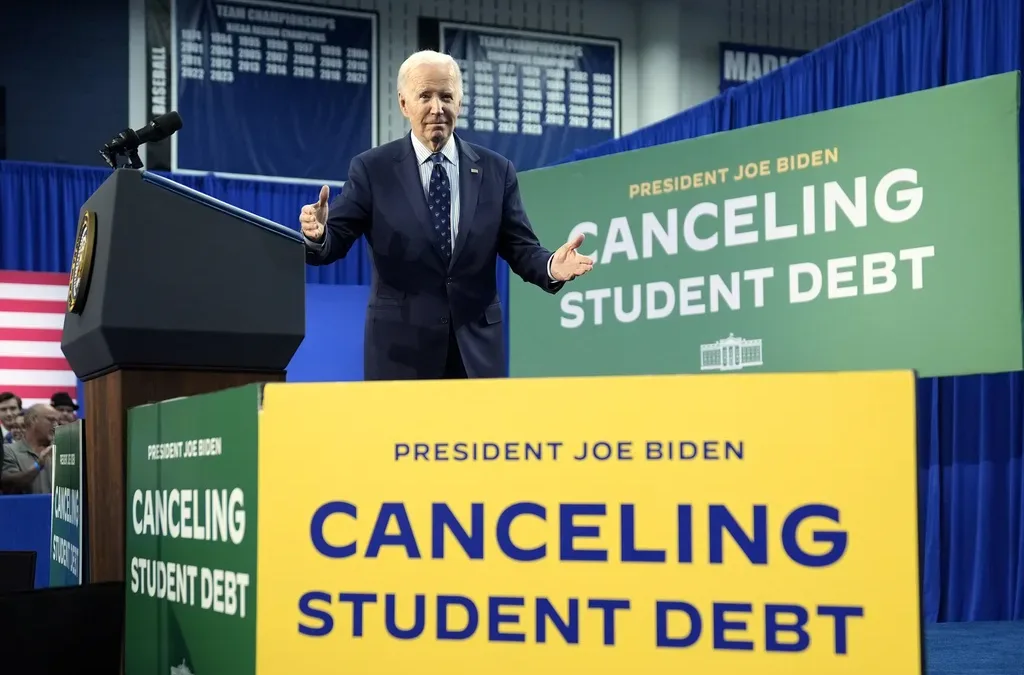

Biden cancels student loan debt for 2,690 more Iowans

The Biden administration on Friday announced its cancellation of an additional $7.4 billion in student debt for 277,000 borrowers, including 2,690...

Local News

No more Kum & Go? New owner Maverik of Utah retiring famous brand

Will Kum & Go have come and gone by next year? One new report claims that's the plan by the store's new owners. The Iowa-based convenience store...

Here’s a recap of the biggest headlines Iowa celebs made In 2023

For these famous Iowans, 2023 was a year of controversy, career highlights, and full-circle moments. Here’s how 2023 went for the following Iowans:...