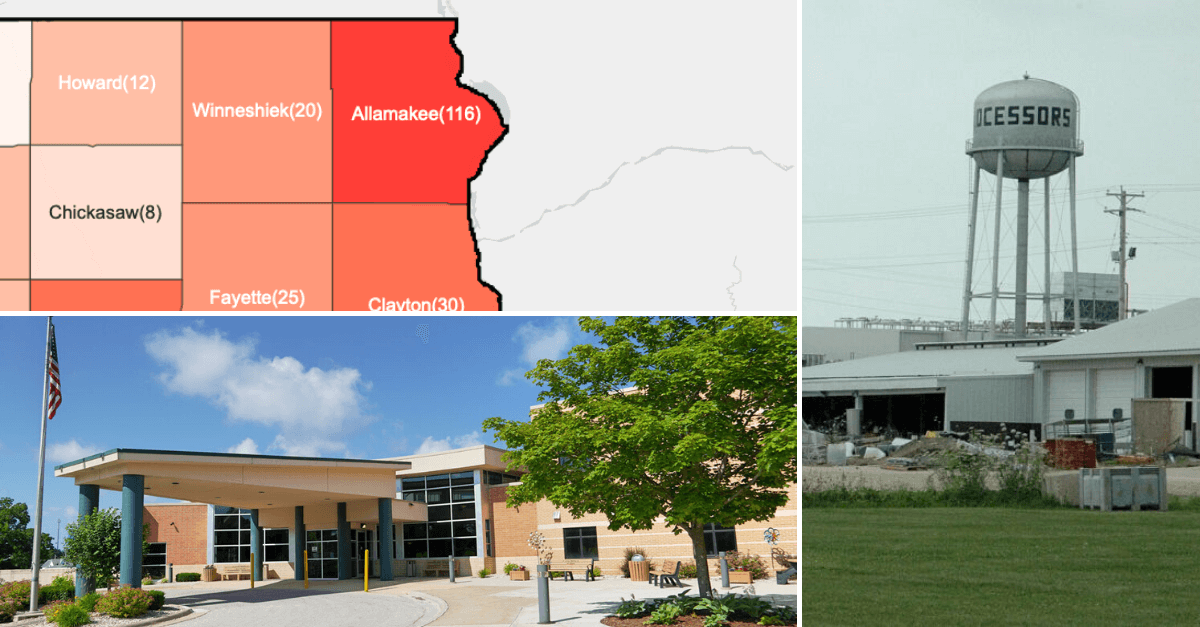

Postville plant photo by Matthew Walleser. Also pictured: Veteran’s Memorial Hospital

When the coronavirus pandemic first struck Iowa, the initial local outbreaks had clear causes. The early spread in Johnson County originated from Iowans returning from a cruise in Egypt. Surrounding counties in Eastern Iowa soon had positive case numbers in the double-digits. Population centers like Polk County quickly followed.

But as attention was focused on these counties, a small, rural one in the northeast corner of the state was experiencing its own very early outbreak. On March 25, Allamakee County counted seven cases of COVID-19, just as many as Linn and Dallas counties had at that stage.

A week earlier, Gov. Kim Reynolds had announced Iowa was now experiencing “community spread.” But with the comparatively high initial numbers in such a small, remote county, locals in Allamakee turned to speculation.

Some said the high numbers must stem from Waukon’s St. Patrick’s Day festivities, part of which continued right before the state imposed its first major rounds of pandemic restrictions.

No, others hypothesized — the virus came when two Jewish Postville residents returned home after traveling to New York City. It’s subsequently spreading throughout the town’s kosher meatpacking plant among the largely Hispanic and African workforce.

[inline-ad id=”1″]

A few communities in Allamakee see a lot of traffic from Black Hawk, Linn and Johnson counties, others suggested, places that also had high early numbers. That’s how it’s spreading.

Chatter, though speculative, only increased within the county of nearly 14,000 as coronavirus numbers continued to soar over the next two months. As of Friday morning, 118 residents have tested positive for the virus. That’s enough to make them the tenth-highest in per-capita cases in Iowa (it was the worst-hit rural county before several meatpacking plant outbreaks elsewhere in mid-April).

Four people have died, including some well-known community members that “spooked” the locals early on, one Waukon councilman said.

State officials said the county’s number of confirmed COVID-19 cases is high because of aggressive testing techniques. At a May 11 daily press conference, Gov. Reynolds attributed the uptick to recent strike force testing at Postville’s Agri Star kosher facility — one of the meatpacking plants in the state to never close its doors during the pandemic.

However, the numbers were already high by then. Only 12 new cases were added from the Postville mass testing; most of Allamakee County’s spike in cases occurred in mid-April.

It also doesn’t appear to be a regional, multi-state outbreak. The cases in the surrounding Minnesota and Wisconsin counties are quite low.

The impetus for Allamakee’s coronavirus spread has been challenging to unearth from tight-lipped officials. And the county’s location on the border of Minnesota and Wisconsin makes a number of health care locations easily accessible for residents, creating more difficulty when tracing the virus.

[inline-ad id=”0″]

Last week, however, Veteran’s Memorial Hospital, located in Waukon, released numbers that showed the virus is largely concentrated in Postville. At that time, 87 of the county’s 112 cases were in the small town in the southwest corner of the county.

That’s where attention has now turned, where it’s believed the outbreak started in the town’s Jewish community and is now prevalent among the Agri Star workforce composed of mostly Guatemalan, Puerto Rican, Mexican and Somalian immigrants. Most who have tested positive are of working age and able to recover easily from the virus, according to health care workers, which explains the town’s low death numbers but high infection rates.

“Most of the COVID cases are healthy in general, working-age people who thankfully don’t have a lot of underlying health problems, so they thankfully have done really well. But it’s gotten out of control, the numbers in Allamakee, because [of a] congregate setting where they work, at a meat plant,” said Jenny Stegen, a Physician’s Assistant at Gundersen Health System, an integrated health care organization in La Crosse, Wisconsin, where some Allamakee patients have sought coronavirus treatment.

The uncovering of this information concerns some Allamakee public health officials, however, who warn residents living outside of Postville, who may have now let their guard down, of subsequent virus spikes.

“In one town in our county that is not necessarily close to where most of the [coronavirus] activity is, we had some businesses that were appropriately masking and had measures in place to reduce and mitigate the spread, but now that they know there isn’t ‘any in their community now’ they have forgone those measures,” said Allamakee County Public Health Director Lisa Moose during a May 13 Board of Health meeting held over Zoom.

“So those are the kinds of things that we’re trying to prevent. Everyone needs to be vigilant. The amount of asymptomatic positive cases that are tested is surprising… That has been very frustrating for us.”

[inline-ad id=”3″]

Facebook comments on various coronavirus-related threads in Allamakee County show the same — people who live in Lansing, 34 miles northeast of Postville, express relief that the county’s main outbreak is away from their community.

As some restrictions have begun to lift in Allamakee, health workers and other county residents have also voiced concern over the accuracy of recorded case numbers in Postville’s population, filled with essential workers who sometimes struggle with language barriers, which makes public health education more challenging.

“I think there are more people sick than the numbers that they are saying, because a lot of people that I know, they don’t even want to go to the hospital because they don’t want to get a bill,” said Rosa Perez, a Guatemalan-American living in Postville, who has some family members working in the plant.

She and her husband believe they had the virus after experiencing symptoms, while her sister-in-law, mother-in-law and grandmother-in-law all tested positive.

[inline-ad id=”2″]

The Postville Outbreak

A drive through Postville displays the unique nature of this rural Iowa town. The town’s main street is lined with Hispanic and Somalian businesses and community centers, while an Orthodox synagogue sits among farmhouses. With slightly over 2,000 residents, Postville is known for its diversity and somewhat evocative past.

Orthodox Jews from New York City came to Postville around 30 years ago, bringing with them a meatpacking plant called Agriprocessors, which grew into one of the United States’ largest producers of kosher meats. The plant attracted a large immigrant workforce, many of whom were undocumented.

Federal agents conducted in 2008 one of the largest immigration enforcement raids to date — leading to the arrest of nearly 400 plant employees and their families. Many went into hiding and a number of others left the country.

After the plant then went bankrupt, it was purchased in 2009 by Hershey Friedman, a Canadian Jewish investor, and continued to run — now under the name Agri Star — and still employs large numbers of immigrants. The number of refugees employed there increased, as their immigration status removes many legal concerns for companies.

[inline-ad id=”4″]

In mid-March, following Allamakee County’s first cases, an Orthodox Jewish news publication reported that three positive cases of COVID-19 were confirmed in Postville and linked with travel from Jewish communities in New York City and Iowa.

“All three cases were in the same family,” read a statement from Agri Star sent to the publication and included “two parents and an older son” who were immediately quarantined upon exhibiting symptoms of the virus back in Postville.

Aron Schimmel, the executive director of Postville’s Chabad Jewish community center, told Starting Line this was the first COVID case he was aware of in town. The couple and their son were in New York celebrating a holiday. Schimmel himself tested positive for the virus — he said his sickness can probably be traced back to when he met with the family after their return to congratulate them on their son’s engagement, which occurred on the trip.

The community restricted trips to New York during the Passover holiday in April, Schimmel said, but travel is set to resume when things start opening up again.

Schimmel said the Jewish community has pretty much recovered from the virus, which impacted around 20 to 30 people — many of whom did not seek medical attention but stayed home in bed with their symptoms.

Aaron Rubashkin, one of the founders of the plant, died at 92 of COVID-19 in New York, which Schimmel said hit Postville’s Jewish community “hard.” One of Rubashkin’s sons still lives in the town.

President Donald Trump in 2017 commuted the 27-year sentence of Rubashkin’s grandson Sholom, the chief executive officer of what was then Agriprocessors. He was released from prison after serving only eight years following charges of providing fake identification for the workers and bank fraud.

[inline-ad id=”5″]

Sholom’s commutation was reportedly pushed for by Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner. The Kushners have longstanding ties to the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, of which Rubashkin was a member of the Hasidic sect.

But no one else from the Postville Jewish community died, Schimmel said, and they haven’t taken much of an economic hit due to the pandemic. Mostly younger people contracted the virus, including about two or three rabbis who work in the plant. He was surprised at the high number of cases in Postville — and suspected they were from the non-Jewish community.

“The plant has continued to operate. At a much slower pace, because a lot of non-Jewish workers are away for some reason. They don’t come. But it’s open and it’s running and they continue to pay the rabbis. So economically, people weren’t hit so much in this area,” Schimmel said.

Plant Workers Forced Into Long Hours As Others Don’t Show

Maria Reyes, whose name was changed for this article so she could speak freely, said she usually soaks her feet in hot salt water at the end of her shifts on the beef keel line at Agri Star. But after getting off a 16-hour shift ending around 10 p.m. on Monday, she just planned on taking a shower and getting in bed. After all, she had to be up at 4 a.m. the next day to do it all again.

“I’m really tired,” said Reyes, who has been working overtime on the chicken keel because other Agri Star workers, who either have coronavirus or are afraid of contracting it, are not showing up to work.

[inline-ad id=”6″]

Over the past two weeks, Reyes said she has worked about 150 hours with no direction from management on when the overtime work will let up — she suspects it will be when people start coming to work again.

Reyes said she and other Agri Star employees want the plant to shut down, like the Tyson Foods facilities in Columbus Junction and Waterloo, among others that closed after severe outbreaks. But when the state ordered a strike team to test over 463 workers on May 5, only 12 positive cases were found.

“[Agri Star] always confirmed that they weren’t closing the plant. Yes, the employees want a closure. Because everybody was freaking out,” Reyes said. “Some had to quit work, some had to stay home for a few weeks. But I felt for sure that it was more than 12, so I was surprised when they said it was only 12 [who had the virus].”

Reyes’s confusion over the number of positive cases at the plant isn’t isolated. Those working closely with COVID-19 patients and members of the most at-risk communities expressed surprise over the low number, which contradicts what they are seeing on the ground.

“Wow. Twelve out of all of those?” Stegen said when she heard the number of confirmed cases. “I was expecting like ten percent of them at least. At least. I was expecting ten to twenty percent of them, like 80 to 100 cases, that’s what I was expecting.”

Schimmel said he thinks the Agri Star plant has been able to stay open because they’ve successfully followed precautionary health methods.

[inline-ad id=”7″]

The plant has hand sanitizer everywhere and everyone is required to wear a mask at work, according to Reyes, but social distancing is difficult when working on the line.

“We’re working together with the government with all the requirements … with all the cleaning and all the precautions, and I saw on the internet that something from President Trump, or from the Governor, that they did not want to close the meat plants in Iowa. Because it’s a very big part of the local economy,” Schimmel said.

“I know in other places, in other slaughtering plants in the New York area they closed down for a while, but here it wasn’t closed for even one day. Because of all the precautions and cleaning and the sanitizing and the masks.”

In late April, President Trump invoked the Defense Production Act, ordering meatpacking plants, which he called “critical infrastructure,” to stay open in order to sustain a “continued supply of protein for Americans.”

“We’ve tried to be a partner throughout this entire COVID pandemic, working with our processing plants, because it is critical infrastructure and they are essential workers and we need to make sure that we can keep them up and running to keep the nation’s food supply flowing,” said Gov. Reynolds at a press conference in April.

According to a new analysis, at least eight meatpacking plants in Iowa have many confirmed positive cases of COVID-19, putting the state No. 1 in the country in its rate of meat industry-related infections. But the governor has warned that if employees do not attend work, unemployment benefits may stop.

[inline-ad id=”8″]

Reyes said that at Agri Star, there is a point system — if an employee doesn’t show up to work or leaves early, management can take away points. If zero remain, the worker will be terminated.

“I didn’t show up to work yesterday, because they started training me on nights, which I’ve never worked before. It was hard for me and my hands were swollen and numb, so I decided I was going to take the day off yesterday because my area wasn’t working, but chicken was working, and they said they were going to take a point from me because I didn’t show up to work, but it’s not my area,” she said.

“I think it’s so unfair because if I’m done with my area, I shouldn’t be forced to stay in a different area and do the job because people don’t want to come to work.”

Agri Star has not responded to Starting Line questions about the testing, how it’s stayed open and employee concerns.

Virus Spreads Through Worker Communities

Currently, Maria’s children are staying with her sister while she continues to work in the plant and is potentially exposed to the virus. She hasn’t seen them in over two weeks.

But it isn’t uncommon for the immigrant workforce at the Agri Star plant to live with extended family members in sometimes small quarters, a factor that could contribute to the further spread of coronavirus in Postville after a plant outbreak, Stegen said.

“Social distancing seems to be more of a foreign concept, just because probably they’re just a very close-knit community over there. Postville’s a very small town, it’s families, friends. Outside of work within their communities, in their close-knit community settings. They’re living with multiple generations, they probably share meals, and they’re often socializing and having get-togethers,” she said.

[inline-ad id=”9″]

Allamakee County public health officials have been working to educate these workforce communities, which sometimes includes overcoming language barriers.

An Allamakee public health staff member and a Gundersen provider, both of whom speak fluent Spanish, have helped “bridge the communication gap during these unprecedented times,” Lisa Moose, Director of Allamakee County Public Health, said. The staff visited businesses in the Postville community to answer any questions they had, as well as to provide them with educational hand-outs, masks, and hand sanitizer.

Moose said they also worked with area clergy, who then shared information with their parishioners. They also worked with a tri-state coalition of public health staff to make videos with COVID-19 educational information in Spanish. And they worked closely with Agri Star’s HR department to ensure signage was posted where needed and in multiple different languages.

The workforce communities have also been more safety-cautious after seeing friends or family members badly hurt by the virus.

Rosa Perez’s 76-year-old grandmother-in-law spent three weeks at the hospital after contracting the virus, but was able to come home last week.

“We saw that my grandma-in-law was going to die, so we’re scared. We’re scared to go to Walmart. If we need something, one of us goes. We don’t even take the kids with us,” Perez said. “We stay home because we went through that and we don’t want to go through that anymore. That was one chance at life that God gave us and I’m scared.”

[inline-ad id=”10″]

Reopening The County

Allamakee is one of 22 counties that was able to reopen restaurants, retail stores, closed malls and fitness centers at 50 percent of the business’s capacity on May 15, two weeks after counties with less virus spread were able to do so.

The stricter restrictions economically hurt Allamakee, which is why in early May the county board of supervisors made a motion to receive the Iowa Department of Public Health county statistics by zip code, on request by At-large Waukon City Council member John Ellingson.

County Supervisor Dan Byrnes said at the Board of Health meeting that the supervisors did this because they wanted to free up some of the towns that don’t have high COVID-19 numbers so that their economies could begin to reopen again.

[inline-ad id=”12″]

Ellingson said that some local businesses were impatiently waiting to reopen — one Waukon restaurant even inquired what the fine would be if they were to resume business before state approval.

But Allamakee Environmental Health Director Laurie Moody said at the Board of Health meeting that the businesses she interacts with are somewhat uneasy about opening up again.

“As much as they want to get open, and need to financially get open, I think they all are still a little on the apprehensive side about the safety behind the facts or the fiction, whatever is floating around. They don’t want to find out that all this stuff is true, and put themselves in harm’s way,” she said.

Jeanne Stein, Board of Health Chair said at their meeting that county residents should continue to wear masks, social distance and wash their hands, even when the county restrictions are lifted.

“The suggestions are such simple things for us to do compared to the grief of people who have lost loved ones are going through,” said Stein. “It’s such an easy thing we can do to help everybody.”

by Isabella Murray

Posted 5/22/20

Iowa Starting Line is an independently-owned progressive news outlet devoted to providing unique, insightful coverage on Iowa news and politics. We need reader support to continue operating — please donate here. Follow us on Twitter and Facebook for more coverage.

Politics

Biden announces new action to address gun sale loopholes

The Biden administration on Thursday announced new action to crack down on the sale of firearms without background checks and prevent the illegal...

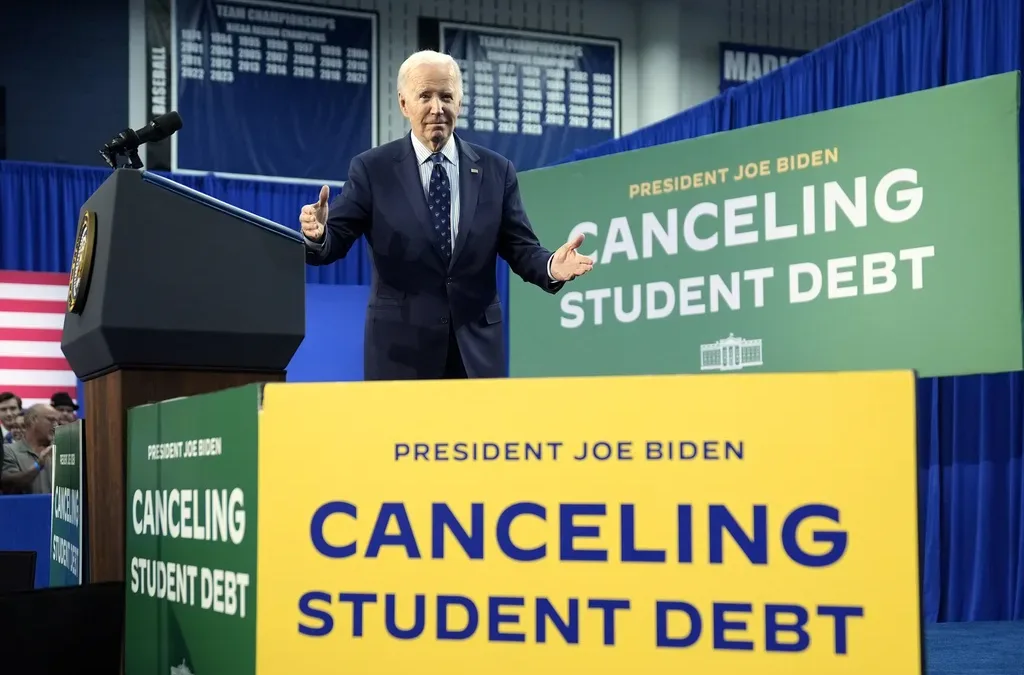

Biden cancels student loan debt for 2,690 more Iowans

The Biden administration on Friday announced its cancellation of an additional $7.4 billion in student debt for 277,000 borrowers, including 2,690...

Local News

No more Kum & Go? New owner Maverik of Utah retiring famous brand

Will Kum & Go have come and gone by next year? One new report claims that's the plan by the store's new owners. The Iowa-based convenience store...

Here’s a recap of the biggest headlines Iowa celebs made In 2023

For these famous Iowans, 2023 was a year of controversy, career highlights, and full-circle moments. Here’s how 2023 went for the following Iowans:...