Places like Iowa Falls feel a long way away from the national discussion on the Democratic primary.

An Iowa town of 5,000 people, it’s a long drive away from any county that even used to vote regularly for Democrats, and the kind of place where Fox News is the default channel running on the TV in every local small business. Situated in the middle of Central Iowa’s farm country, Iowa Falls’ Hardin County was one of many rural counties to vote lopsidedly for Donald Trump in 2016. Hillary Clinton received only 33% of the vote here.

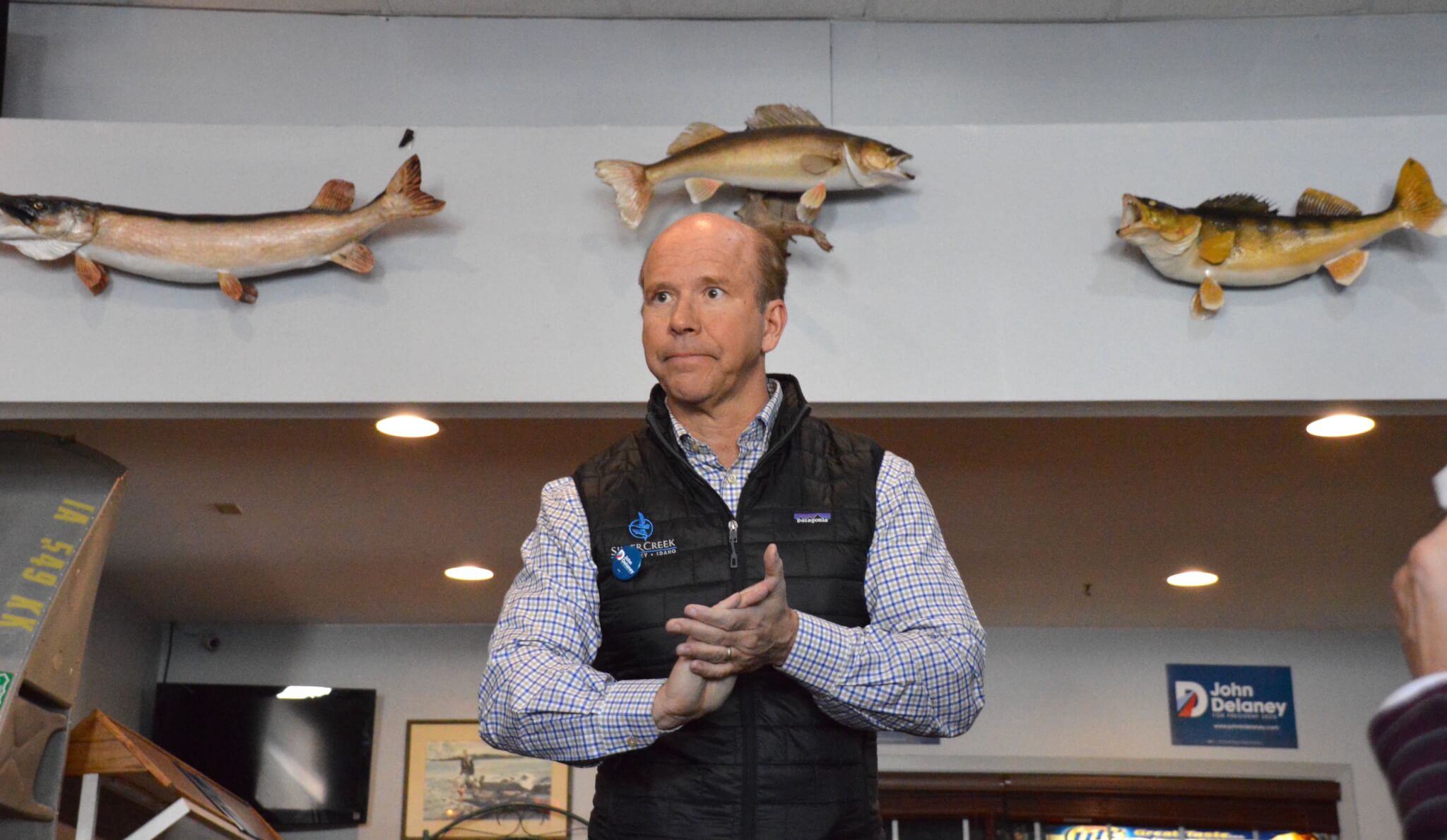

That’s where presidential candidate and former Congressman John Delaney found himself late last month, pitching his brand of “pragmatic idealist” to a group of local Democrats.

“The 2020 election is going to be won in the center with a candidate who can appeal to people who could go either way,” Delaney asserted to about a dozen Democrats in a side room of a tavern. “They want someone to put their country first.”

It was part of Delaney’s more explicit case that he’s been making lately about electability in 2020. And he’s found receptive – or at least understanding – audiences for it as he makes his second 99-county tour across Iowa, visiting many rural, heavily-Republican counties long before other candidates do.

“I do consider myself a pragmatic idealist, which means I’m more centrist, which means I’m more moderate, which means I’m more of a problem solver,” Delaney told Starting Line during a past interview.

The national Democratic Party’s reputation is a tarnished one in small Iowa towns, due to all kinds of cultural, political, racial, economic, and tribalism trends that were only exacerbated by Trump. And unlike for Democrats in larger cities, people here can’t simply surround themselves with mostly like-minded individuals.

Democrats like Monica Peitz, 64, who came out to see Delaney in her town of Perry back in February, are used to hearing what her neighbors and friends have to say about the party. One word that often comes up these days: “socialism.”

“I see people comparing it to Venezuela,” Peitz said of Democrats’ health care expansion plans. “Just in Facebook comments, you see people talking about these programs turning us into Venezuela. It’s ridiculous … There needs to be an aggressive campaign to separate out how the extension of programs we already have is not going to turn us into a socialistic country.”

Those kinds of conversations and framing – online and in person – have made elections difficult for Democrats here. And while the past presidential results in these counties are one thing, what’s more personal to grassroots activists is how their local candidates have fared. Even when Democrats find an excellent, qualified person to run for the state legislature, it doesn’t matter how hard local volunteers and the candidate work. The result is always the same: wipeout.

In places like Iowa Falls, some of the local Democratic activists feel like they’re living in a different world than their neighbors.

“Every once in a while, we’ll go to a friend’s house and watch Fox and we can’t believe what we’re seeing,” explained Ron Rickels of Iowa Falls, who came out to ask Delaney questions last month. “What is this?”

[inline-ad id=”2″]

Still, many Iowa Democrats think there are still opportunities here. Barack Obama came within seven points of Mitt Romeny in Hardin County in 2012, and the party has been looking for ways to at least cut down on the margin of losses in rural Iowa.

“The hardcore Republicans aren’t going to change, but I see some of my neighbors shaking their head at what Trump’s doing,” said Lynn Brinkmeyer, a retired substitute teacher from Hubbard, a town of less than 200 people in Hardin County.

The challenge for Democrats is countering the negative national image that’s taken hold in these communities.

Delaney aims to avoid those frames altogether if he’s the nominee. The son of an electrician who went to college with the help of an IBEW union scholarship, Delaney found significant success in the business world as the CEO of a commercial lender and a health care financing company. On the campaign trail, he pitches capitalist innovation as the solution to many American problems – so long as there’s a strong safety net for workers negatively impacted by change.

Any Democratic nominee will get hit with the “socialist” label, but with Delaney’s background, the hope is that it won’t stick. And he’s driven that point home whenever he could this year.

When Bernie Sanders announced his second presidential run in February, Delaney’s campaign fired off a shot at the Vermont senator in a statement.

“This primary is going to be a choice between socialism and a more just form of capitalism,” Delaney said. “I believe in capitalism, the free markets, and the private economy. I don’t believe socialism is the answer and I don’t believe it’s what the American people want.”

The “socialism” debate has swirled around national politics this year with the new Democratic House majority and some of the more left-leaning presidential candidates. Delaney’s bet is that it’s not what’s driving most conversations on the ground in Iowa.

“When we talk about Medicare for all, it kind of scares me,” one man in Perry told Delaney, explaining his work in the health care industry and how difficult it got to navigate the current system for supplements.

[inline-ad id=”0″]

Beside the labels, Delaney also pushes back on what he sees as the basic feasibility of some plans.

“I think proposals that call for a single-payer healthcare, that makes the government the only payer and effectively throws out one sixth of the economy and starts from scratch – it’s not about whether it’s socialism or not, it’s just a wildly impractical proposal,” Delaney told Starting Line in February. “And it’ll actually make healthcare worse in this country because the government has never been proven to pay the cost of healthcare – both Medicaid and Medicare pay below cost.”

That’s not, however, what an important and growing segment of the Democratic Party wants to hear right now. Younger and more progressive voters are increasingly in favor of sweeping government initiatives to ensure health care coverage – not just access – for everyone. They view words like “affordable” health care with skepticism, and look favorably at candidates who embrace the term “socialism” (or perhaps “democratic socialism”).

Meanwhile, Delaney is proposing a fully bipartisan first 100 days in office, where he says he’d only push for bills that could get some Republicans on board. He lists criminal justice reform, immigration, infrastructure, national service, and digital privacy as potential early legislative wins in his presidency. Delaney also doesn’t favor major a Supreme Court restructuring. Democrats fed up with obstructionist Republicans may view that as either naive or unrealistic in today’s political climate.

There’s a risk, many caution, that a Democratic presidential nominee who fails to excite or appeal to those progressive voters will fail to turn them out. Just look at how Clinton was damaged by low turnout or large third-party defections among younger voters in 2016.

But the election results that Delaney is looking at is from 2018.

“President Trump is going to turn out his supporters in record numbers. Democrats are going to turn out in record numbers. Whether it’s me or any of the 17 people I’m running against,” Delaney said in Iowa Falls. “You know why? Because you all are going to be motivated. You all are going to get out to vote. And President Trump is going to remind people why we have to vote.”

“[In 2018], some districts we ran young people,” he continued. “Some districts we ran people who are older. Some districts we ran socialists. In other districts, we ran people who were really moderate. Some districts had a white person, black person, woman, or a man. Didn’t matter what we ran, the turnout was high. So, the 2020 election is going to be about the center. The fastest growing part of the electorate is independents, unaffiliated voters. 2020 is going to be won in the center.”

In his electoral theory, Delaney sees the Democratic base turning out no matter what to oppose Trump. And if you look back to the governor’s race in Iowa last year, the problem Democrats faced wasn’t from lackluster turnout in liberal hubs like Iowa City, Des Moines, or Ames – those places gave the party historic margins. It was blue-collar and rural Iowa that sunk Democrats’ hopes.

For his immediate Iowa Caucus goals, Delaney has campaigned extensively in rural Iowa, among the very Democratic activists who might worry about the down-ballot impact the party faces in their towns if the nominee is too easily caricatured.

“He strikes me as a person with a moderate approach to some problems, and I really feel strongly that’s what we need,” Jay Pattee, 66, of Perry said after watching Delaney speak. “He would be someone that I’d consider voting for, not to say I won’t consider others as well.”

“He brings forth very good points on bipartisanship,” noted Brinkmeyer in Iowa Falls. “Bring it together, don’t divide us. Don’t tweet us apart.”

Even some Iowans who would prefer a more progressive candidate are still considering the electability issues that Democrats like Delaney are pitching.

“It literally makes me sick that we’re even thinking this way. We should be thinking of who is best for the country,” lamented Rickels in Iowa Falls. “It’s really sad that my mind goes to what’s the name that Trump is going to call this person? Who can withstand the barrage that he or she is going to get?”

Of course, Delaney’s strategy is not one that grabs national headlines every few days. He’s been running for president since July of 2017, but rarely breaks through in any given day’s news cycle, especially now that so many other Democrats have joined the race.

One recent Iowa poll, however, showed a bit of movement for Delaney. A Focus On Rural America survey in March placed Delaney at 3% in Iowa, above several senators, governors, and past cabinet members. That same poll had 66% of Iowans preferring a candidate who worked on economic development issues in rural America.

When it comes to caucus math, Delaney’s rural approach could serve him well. Because each precinct in Iowa has a set number of delegates they elect, a candidate can’t simply run up the totals in Iowa City. And getting to 15% viability in the precincts with large turnouts in the cities can sometimes take over 100 people, not an easy task for any campaign. Just turning out 10 or 15 people in a rural precinct, however, can get you to viability. Delaney’s busy travel schedule and large field team gives him an advantage there, even if he’s not the most visible Democrat on cable news.

Getting to a sizable caucus night percentage, something big enough to catapult him into contention in later states, will still take more than that. Delaney needs a moment just like everyone else. But he at least has a possible foundation and fully-formed strategy to get him a base of support in Iowa.

“My strategy is to do what I’ve done my whole life, which is to grind it out, work harder than everyone else, and talk about things that make sense,” Delaney said.

by Pat Rynard

In-story photos by Julie Fleming

Posted 4/20/19

Politics

Biden marks Earth Day by announcing $7 billion in solar grants

The Biden administration on Monday announced the recipients of its Solar For All Program, a $7 billion climate program that aims to lower energy...

6 terrifying things that could happen if the Comstock Act is used to target abortion

Does 1873 sound like a really, really long time ago? Well, that’s because it is—but if Republicans and far-right anti-abortion activists have their...

Local News

No more Kum & Go? New owner Maverik of Utah retiring famous brand

Will Kum & Go have come and gone by next year? One new report claims that's the plan by the store's new owners. The Iowa-based convenience store...

Here’s a recap of the biggest headlines Iowa celebs made In 2023

For these famous Iowans, 2023 was a year of controversy, career highlights, and full-circle moments. Here’s how 2023 went for the following Iowans:...