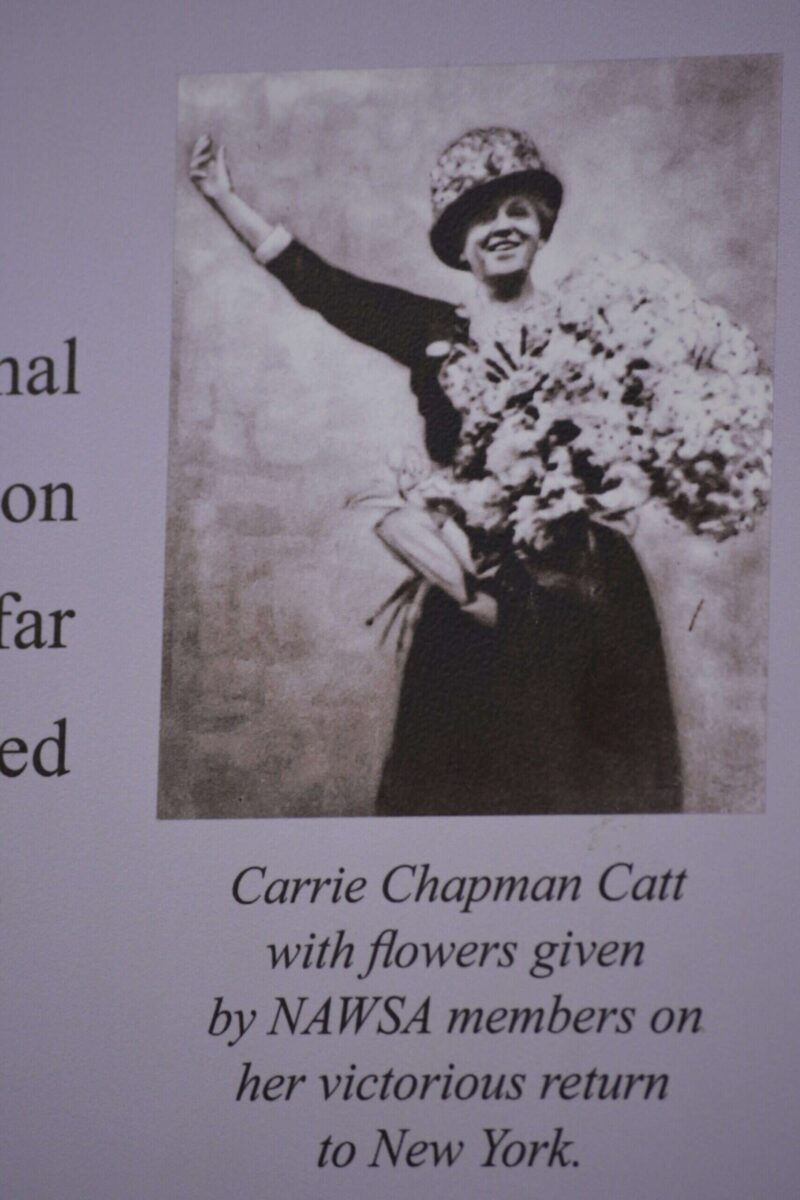

Carrie Chapman Catt, celebrating her campaign's victory. (Amir Abouelw/Shutterstock).

Arabella Mansfield, Getrude Rush, Edna Griffin, and Carrie Chapman Catt made history in Iowa and beyond. Here are their stories.

Iowa is known for being a place of progressive ideals. Many women throughout history who have called this state home have used their lives here to establish widespread change. From Arabella Mansfield, who became the first white woman to pass the bar in Iowa, to Edna Griffin, who fought for racial equality in the 1940s, these individuals worked against the laws of oppression to create a brighter future for everyone. They advocated for themselves and others during times when it was socially unacceptable and often dangerous to do so. They didn’t back down from the challenge, though, and we are all better off because of their tenacity.

Though I’ve done my best to provide a broad overview of these women’s accomplishments, I’d encourage you to do your own research as well. So often, we are only presented with brief snapshots of history, which are important in their own right, but they do not tell the full story. Every woman on this list, and countless others who I wasn’t able to highlight due to time and word constraints, is deserving of your undivided attention. They fought against obstacle after obstacle to ensure that we all have the freedoms we deserve—and many, many new pioneers are still working to this day to make sure that remains the case.

Arabella Mansfield

History was made in Iowa in 1869 thanks to the dedication and determination of Arabella Babb Mansfield. Mansfield—who was born in Des Moines County’s Benton Township in 1846—challenged the state’s law regarding the Iowa bar exam. Before 1869, the law stated that only men over the age of 21 were permitted to take the test. For Mansfield, this restriction was unacceptable. She had been studying law for over two years; her brother, Washington Babb, had his own law practice in Mount Pleasant, and he allowed Mansfield to study as an apprentice there in preparation for the exam.

Before she decided to take on the law, Mansfield had studied at Iowa Wesleyan College in the early 1860s. She graduated as valedictorian after three years and went on to teach in Indianola at the Des Moines Conference Seminary, which is now known as Simpson College. She left the position to wed John Melvin Mansfield, whom she met in college, and who was teaching at their alma mater at the time. John encouraged Arabella to pursue her interest in studying law, and her brother agreed.

Arabella was also assisted in her goal to take the bar exam by Judge Francis Springer, an advocate for women’s rights. He found a legal loophole in the way Iowa Code § 3.29(3) was written, and said that it was never meant to exclude females. In taking this stance and changing the licensing statute, Iowa became the first union state to permit women and minorities to practice law. Arabella took the exam and passed with high scores, going on to be sworn in at Mount Pleasant’s Union Block building later that same year.

Perhaps the most impressive aspect of Arabella’s ambition is that she did not ultimately end up practicing law. Being able to take and pass the bar exam was something she wanted to do as a personal goal and as a way of establishing gender equality in Iowa. After passing the bar, she taught first at Iowa Wesleyan College before eventually moving to Indiana to teach at DePauw University. Later in life, she served as DePauw’s Dean of the School of Art in 1893 and its Dean of the School of Music in 1894. Arabella also chaired the Iowa Women’s Suffrage Convention in 1870 alongside Susan B. Anthony.

Fun Fact: The first female lawyer permitted to take the bar exam on the West Coast, Clara Foltz, was also from Mount Pleasant and grew up in the area around the same time as Arabella Mansfield.

Gertrude Rush

Though Arabella Mansfield’s efforts made Iowa’s laws more inclusive for white women, it wouldn’t be until Gertrude Rush came along that things began to change for women of color as well. Gertrude graduated from Des Moines College in 1914 and went on to study law under her husband, James B. Rush, who was an attorney. She, like Mansfield before her, wanted to create a world where equality was available to everyone in Iowa. In 1918, Gertrude became the first Black woman to pass the bar and the first to officially practice law in the state.

Despite this crowning achievement, though, she was not permitted membership to the American Bar Association when she applied for membership in 1924. Refusing to back down in the face of discrimination, Gertrude worked alongside George H. Woodson, James B. Morris, Sr., S. Joe Brown, Charles P. Howard, Wendell E. Green, Jesse N. Baker, George C. Adams, Charles H. Calloway, L. Amasa Knox, C. Francis Stradford, and William H. Haynes, establishing the Negro Bar Association with four other lawyers. The following year, in 1925, it was officially dubbed the National Bar Association.

Gertrude was the only Black woman in Iowa to practice law until Willie Stevenson Glanton moved to Des Moines in 1953. Gertrude devoted her life and career to civil rights endeavors, often fighting to ensure that Black lawyers were given access to the books, education, and opportunities they rightfully deserved but were not always granted.

Edna Griffin

Edna Griffin’s historical significance is perhaps best described by writer Jessica Lowe: “Prior to almost every major event in the Civil Rights timeline taught in classrooms; there was an Iowan beginning her own fight for equality—Edna Griffin.” Griffin’s pioneering fight for equality began in earnest on July 7, 1948. She, along with her infant daughter Phyllis and two men named Leonard Hudson and John Bibbs, stopped at Des Moines’ Katz Drug Store. It was a particularly sweltering summer day, and Griffin asked for an ice cream soda when the group entered the store. They were refused service, though, as the manager informed them, “It is the policy of our store that we don’t serve colored [people].”

Hudson, Bibbs, and Griffin were already active members of Iowa’s Progressive Party and had been fighting against discrimination in their local communities when the incident took place. After they were refused service, Griffin took matters into her own hands and organized sit-ins, boycotts, and picket lines every Saturday in front of the Katz Drug Store, where she was joined by many others. This went on for about two months before she, Bibbs, and Hudson ultimately decided to file charges against Maurice Katz, who owned the store, in November 1948. The group said that Katz violated Iowa’s 1884 Civil Rights Act, which prohibited discrimination in public spaces.

Katz was then brought to trial in a landmark case, State v. Katz, where a jury found him guilty, and he was ordered to pay a $50 fine. He filed an appeal with the Iowa Supreme Court for his conviction, and during this time, Griffin filed a civil suit for $10,000 in damages at the Polk County District Court. In December 1949, the Iowa Supreme Court upheld Katz’s conviction. During the civil trial in Polk County, Griffin pleaded her case to an all-white jury, who took her side in the matter but only awarded her $1 in damages. Her lawyer, who was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)’s Legal Defense Fund, said that it was a victory of morals more than anything else.

Because of Griffin’s actions, Iowa laws were changed to ensure that African-Americans were served and accommodated at restaurants, inns, soda fountains, theaters, and other establishments across the state.

Carrie Chapman Catt

The road toward the 19th Amendment was initially paved by Iowa native Carrie Chapman Catt. She first became frustrated by voting laws in 1872 when, at the age of 13, she noted that her father was permitted to vote but her mother was not. Catt carried this frustration toward inequality throughout her life, until she eventually became involved in the Iowa Woman’s Suffrage Association in the 1890s. She lectured across the country regarding women’s rights, and went on to be voted the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1900, and then again in 1915.

It was during her second presidency of the association that she began her campaign to amend the US Constitution to grant women the legal right to vote. She worked tirelessly alongside the women’s suffrage movement for several years until President Woodrow Wilson expressed his support for the cause. After President Wilson’s endorsement, Congress passed the 19th Amendment on June 4, 1919, but Catt’s mission wasn’t over. She worked for several more months to ensure the amendment was ratified in each state; it was eventually adopted into the US Constitution in August 1920.

When speaking about the history of the 19th Amendment and the accomplishments of Carrie Chapman Catt, it’s equally important to draw attention to the fact that women of color were not granted the right to vote when that amendment was adopted, despite the fact that they also fought for this right during the women’s suffrage movement. Native Americans were not even permitted to be US Citizens until the Snyder Act was passed in 1924, which then allowed some Native peoples to vote. It wasn’t until the 1960s that Native Americans, as well as Black Americans, were finally given the right to vote across the country. Asian Americans gained the right to vote in the 1950s, and Latin American women were granted the right in the 1930s.

For more information on women’s voting history as a whole, and the women of color who are equally deserving of recognition but are often erased by history, you can check out these articles from PBS and the California Commission on the Status of Women and Girls.

Former Iowa legislator writes children’s book on fleeing war in Bosnia

Anesa Kajtazović, who served in the Iowa Legislature from 2011 to 2015, talks to Iowa Starting Line about her new memoir. Several times during our...

The woman who prompted Ernst’s ‘We’re all going to die’ remark is running for Iowa House

The woman who told Sen. Joni Ernst that "people will die" if she votes to cut Medicaid said the senator's mock apology a day later was "deeply...

15 fascinating facts about Iowa-born John Wayne on his birthday

Discover 15 fascinating fun facts about Iowa's Western treasure, the one and only John Wayne. Move over cornfields and state fairs, Iowa’s got...

8 activists from Iowa who changed the game

Iowa has a rich history of activism that dates back centuries. Check out these eight heroes who have fought for all types of underrepresented...

In Walworth County, neighbors rallied for rides—and rediscovered what it means to be a community

When I was a new mom, I wanted nothing more than to move out into the countryside with my baby. I had been raised in mostly rural places and have...

10 facts about Cedar Rapids native Elijah Wood on his birthday

Elijah Wood is one of Eastern Iowa’s connections to Hollywood. Here are 10 compelling facts about the famous Iowan: The 5-foot 6-inch actor with...