A crop duster flies over a field. (Francesca Daly/Courier)

A version of this story first appeared in the Aug. 5 edition of the Iowa Starting Line newsletter. Subscribe to our newsletter to get an exclusive first look at a new story each Tuesday in our The Hot Spot: Investigating Cancer in Iowa series.

Correction: Iowa produced 2.5 billion bushels of corn in 2023. An earlier version of this article used an incorrect figure. A section addressing a 2015 decision by IARC has also been adjusted to reflect the content of the decision.

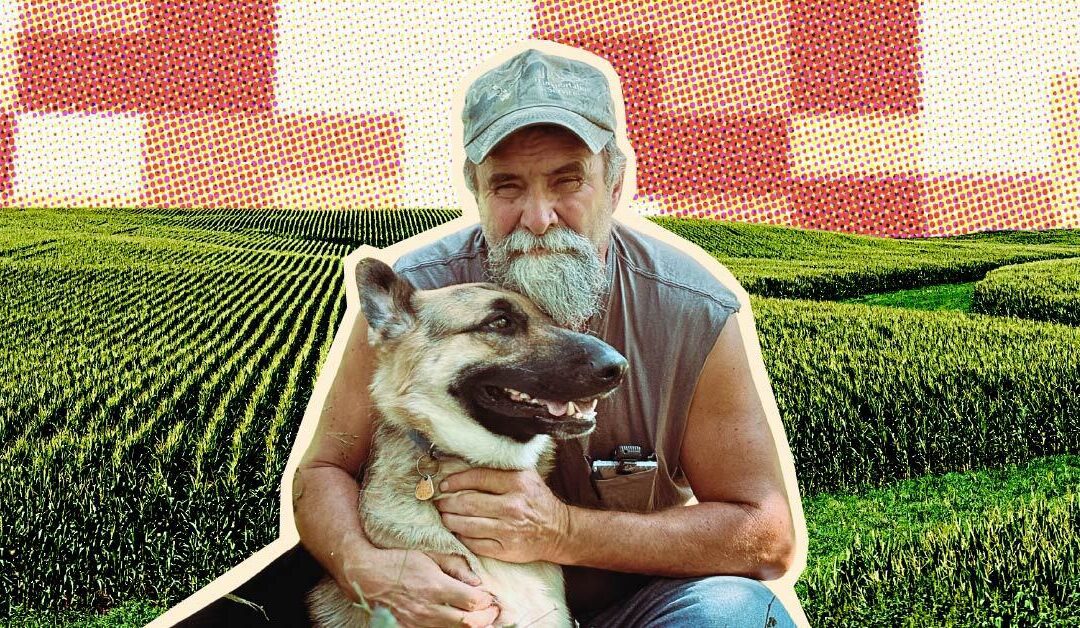

Don Carpenter remembers when farming looked different. Growing up on his family’s 160-acre dairy farm in Cascade, Iowa, he remembers watching his father apply pesticides for about a month each spring: a seasonal ritual that seemed manageable, contained.

“It’s what you did,” the 54-year-old Carpenter said. “You didn’t know any better.”

The north fork of the Maquoketa River winds through Cascade on its way through Dubuque County. Along its length, acres of farmland stretch on, row by row on either side of the river.

“Every time that plane goes over and comes near the river, I just shake my head,” he said. “I understand you have to take care of the corn, but, it just drives me nuts that they’re spraying (pesticides) so close to a body of water.”

From family farms to chemical dependence

Thirty million acres—nearly three-fourths—of Iowa’s area is used for crops and rotational pastures, according to the US Department of Agriculture’s 2022 Census of Agriculture. While the number of farms in the state has decreased, these operations and their size have grown dramatically over the years. In 1950, the average farm size in Iowa was 169 acres. By 2012, the average farm size was 345 acres; it had doubled.

Carpenter said he’s watched these “super farms” buy out family operations like his.

The growth in these operations was powered by advances in technology: tools like GPS-guided tractors and soil sensors, as well as massive increases in the pounds of pesticides applied to farmland.

In 2023, Iowa produced 2.5 billion bushels of corn for grain production—the most of any state in the country. Farmers apply herbicides to 96-97% of corn acres annually. More than 53 million pounds of pesticides are applied across the state each year, according to Food & Water Watch (FWW) analysis of the USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service data.

Pesticides encompass a range of chemicals that control any number of unwanted organisms: herbicides, which eliminate or inhibit the growth of unwanted plants; fungicides, which do the same to fungus; and insecticide, which gets rid of bugs.

Pesticides are applied multiple times during the growing season to limit weeds and harmful insects. The very corn in the field is genetically engineered to be resistant to particular formulations of pesticides.

“Iowa farmers spread more pesticide, fertilizer and manure than any other state,” said Jennifer Breon, an Iowa organizer with Food & Water Watch.

Pesticides are part of why Iowa’s fields are so productive. Research into pesticide exposure also connects them to our cancer crisis.

READ: The Hot Spot: What’s behind Iowa’s cancer crisis?

Science linking certain pesticides to cancer

Iowa Starting Line spoke to researchers ranging from oncologists to toxicologists, most of whom pointed to The Agricultural Health Study (AHS) as the highest quality study of agricultural exposure and its impact on health. Since 1993, the study has tracked 89,000 farmers and their spouses across Iowa and North Carolina. In general, participants in the AHS had lower overall cancer incidence, attributed to low rates of smoking and increased physical activity.

However, a 2019 review of two decades of AHS data found agricultural exposures led to a disproportionate rate of prostate cancer among these farming couples, which supported an earlier analysis in 2011.

According to the 2025 Iowa Cancer Registry, prostate cancer accounted for 14% of Iowa’s new cancers, almost as common as breast cancer. The AHS also found these couples suffered from elevated rates of lip cancer, certain B-cell lymphomas like multiple myeloma, acute myeloid leukemia (AML), thyroid cancer, testicular cancer, and peritoneal cancer.

The most widely used of our herbicides is glyphosate. It’s found in products like Roundup, which was manufactured by Monsanto until Bayer bought the company in 2018. It’s estimated that 16 million pounds of glyphosate-based herbicides are applied in Iowa each year.

In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) reviewed a range of peer-reviewed studies focused on potential glyphosate health impacts. They included studies that found associations between glyphosate exposure and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). The team of cancer scientists issued a decision that glyphosate was “probably carcinogenic to humans.” One meta-analysis published after the IARC review found that glyphosate-based herbicides were associated with a 41% increase in NHL risk.

Despite the growing evidence of its connection to cancer, the chemical remains in wide use. The US Environmental Protection Agency said it is “unlikely to be a human carcinogen.” The federal agency is currently updating its evaluation of glyphosate’s carcinogenic potential.

And that’s part of how the process works: the slow grind of regulators taking in and sometimes adjusting to what research says.

Minding the regulatory gap

Dr. David Cwiertny is the director of the Center for Health Effects of Environmental Contamination at the University of Iowa. He has spent years tracking how agricultural chemicals move through Iowa’s environment.

“Take atrazine,” Cwiertny said.

It was one the most commonly used pesticides in the state. The AHS initially found no strong associations between it and cancer in a 2011 assessment. But the science doesn’t stop once chemicals reach the marketplace. The same researchers, using the same study population, but with additional years of data, published revised findings in 2024 showing atrazine use was associated with lung and multiple other forms of cancer.

“It just goes to show—it’s the same study, the same authors, and a completely different takeaway,” Cwiertny said. “The science doesn’t stop and we get better at detecting occurrences and problems that could be associated with those occurrences.”

But regulation doesn’t automatically adjust to the most recent science. It’s not even standard across nations. A 2019 paper found that of the 1.2 billion pounds of pesticides used in the United States in 2016, 322 million pounds were pesticides banned by the European Union; 40 million were pesticides banned in China; 26 million were banned in Brazil.

This evolution in understanding creates what Cwiertny calls a “gray area” where policy still considers something safe while emerging science suggests it may not be. That lag between scientific discovery and policy is time in which vulnerable populations continue to be exposed to something that could be harming them.

Cwiertny’s team measures pesticide concentrations in waterways, air, and dust throughout agricultural regions. He said they rarely find a water sample that doesn’t contain at least one or two major chemicals, even in remote areas—what Cwiertny calls “ubiquity” that reflects decades of sustained use.

Charles Benbrook is an agricultural economist who has advocated against the increased application of chemicals like glyphosate. He has called for the EPA to not approve chemicals based on limited exposure scenarios, but based on the widespread, repeated use that is seen across states like Iowa.

“The pesticide risk assessment and regulatory decision process as carried out by EPA and its sister regulators in the state… is basically broken,” Benbrook said.

He was most recently in Iowa advocating against a bill that would restrict the ability of individuals to sue pesticide manufacturers like Bayer for health issues, such as cancer, that could be linked to the companies’ products.

An analysis by Food & Water Watch found that since the bill was first introduced in 2023, Bayer has spent $209,750 lobbying for it, including registering seven Iowa lobbyists. That is 5x what they spent in the two cycles prior; and nearly double what Bayer spent lobbying in Iowa in the decade prior from 2013-2023. The bill failed but will likely be back on the table in next year’s session.

The challenge for public health researchers is that this exposure creates a complex web of risk factors that defy simple cause-and-effect relationships. Unlike clear-cut cases of occupational exposure or accidental releases, the kind of chronic, low-level exposure most Iowans face makes definitive connections nearly impossible to establish.

“Here in Iowa, the challenge is there’s a variety of risk factors and it’s not any one thing,” Cwiertny said.

For Don Carpenter, this is an unsatisfying reality. He lives near the Maquoketa River, and each summer, he watches as planes spray cornfields that border its waters.

“ I just want one person. I don’t care which political party, but I just want one person to be like a dog with a bone and just keep harping on this, that we need to do something about it,” he said. “And I don’t have faith in any of them that they can do that.”

Amie Rivers contributed reporting to this article.

[Reporter’s Note: We’re not done with pesticides or agricultural impacts in Iowa. A future entry in this series will touch more on how our regulatory environment could change to limit the exposure Iowans face each year. Stay tuned.]

Support Our Cause

Thank you for taking the time to read our work. Before you go, we hope you'll consider supporting our values-driven journalism, which has always strived to make clear what's really at stake for Iowans and our future.

Since day one, our goal here at Iowa Starting Line has always been to empower people across the state with fact-based news and information. We believe that when people are armed with knowledge about what's happening in their local, state, and federal governments—including who is working on their behalf and who is actively trying to block efforts aimed at improving the daily lives of Iowan families—they will be inspired to become civically engaged.

Surviving cancer in Iowa: Caregivers, advocates share their stories

Cancer in Iowa isn’t just about the research studies and the statistics. Real Iowans and their families are behind each diagnosis. Read our first...

We sent Iowans nitrate tests to check their water. Here’s what they found

This story first appeared in the Sept. 30 edition of the Iowa Starting Line newsletter. Subscribe to our newsletter to get an exclusive first look...

How can policymakers help reduce Iowa’s cancer rates?

This story first appeared in the Sept. 23 edition of the Iowa Starting Line newsletter. Subscribe to our newsletter to get an exclusive first look...

Fighting a health insurance denial? Here are 7 tips to help

By: Lauren Sausser When Sally Nix found out that her health insurance company wouldn’t pay for an expensive, doctor-recommended treatment to ease...

Iowa leads the nation in binge drinking—and faces higher cancer risks from alcohol

This story first appeared in the Sept. 16 edition of the Iowa Starting Line newsletter. Subscribe to our newsletter to get an exclusive first look...

What you can do to reduce your cancer risk: The big six for Iowans

A version of this story first appeared in the Sept. 9 edition of the Iowa Starting Line newsletter. Subscribe to our newsletter to get an exclusive...