Graphic by Keith Warther

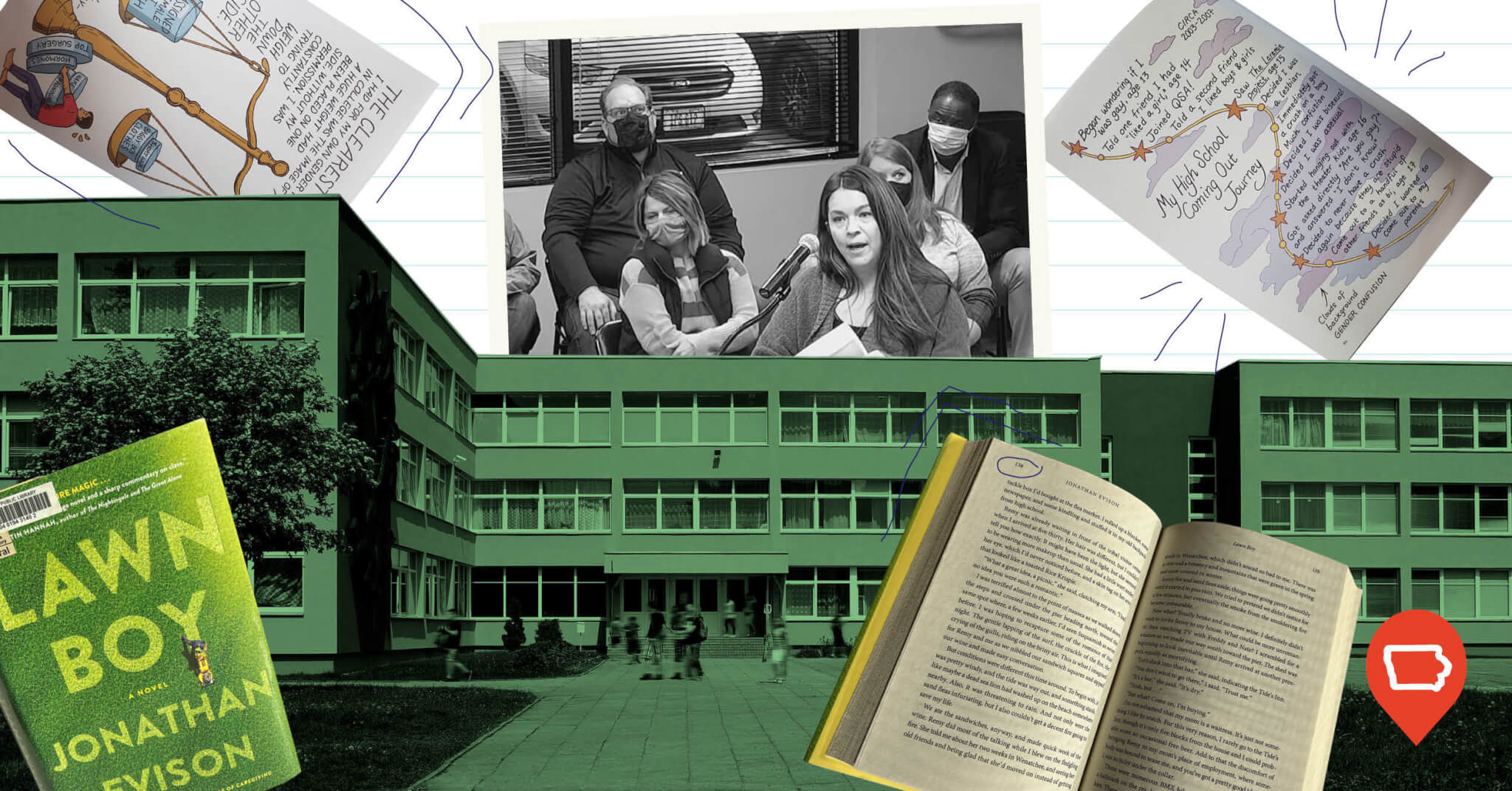

You’ve likely seen the outrage videos and news coverage spreading around Iowa social media in recent weeks: LGBTQ characters—and specifically LGBTQ sex—in books that are available in Iowa high school libraries.

Parents and members of the public have shown up at school board meetings to read sexually explicit passages from the books and insist the school board remove the books from schools. They have often made over-broad, out-of-context, and sometimes outright-false claims about scenes they’ve flagged.

What’s Happening

At a Waukee school board meeting in late October, a woman read excerpts from the memoirs “All Boys Aren’t Blue” by George M. Johnson and “Gender Queer” by Maia Kobabe, and from the novel “Lawn Boy” by Jonathan Evison.

This appears to be the first major complaint this fall, and complaints have spread about other school districts such as Urbandale and Ankeny.

The woman focused on scenes in the books that mention sex. In each case, the scenes make up a handful of pages out of hundreds, or in one case, a single paragraph.

In that book, “Lawn Boy,” the adult character thinks briefly about experimenting with a childhood friend in the past. The scene is 32 words long. In the next chapter, the author remembers having sex with a woman. The scene is also only one paragraph—119 words—long. There has not been much outrage with the straight sex scene.

Later in the book, the character mentions the experimentation a few times, as an important character moment, but it doesn’t happen again.

[inline-ad id=”1″]

What The Books Are About

“Lawn Boy” is a coming-of-age novel about a 22-year-old Mexican-American man who’s trying to figure out how to achieve the American Dream while stuck doing menial jobs. The book focuses on how his fortunes change one opportunity and one pitfall at a time.

“All Boys Aren’t Blue” is a memoir told through a series of essays about the author’s experience growing up Black and gay. It tackles issues of identity, family, consent and marginalization. The scene brought up at school board meetings is a description of the author’s sexual assault by an older cousin when they were underage. Johnson says they knew it was wrong at the time, but they couldn’t stop it happening.

The scene includes and is surrounded by more context than the woman shared during the school board meeting. The whole chapter revolves around Johnson’s conflicted emotions during and after the assault, but the author clearly calls it abuse and shares their struggle to process it.

Some critics have used the passage to suggest schools have books that promote incest. But that’s not the case at all.

Read this paragraph that ends the chapter:

The author wrote about other traumatic events in their life, including family deaths and having their teeth kicked out by bullies, so this content isn’t a departure from the overall topics in the book.

[inline-ad id=”3″]

“Gender Queer” is a graphic-novel memoir about growing up not understanding why boys and girls are treated differently, and how gender roles and expectations don’t feel right to the author. Kobabe writes about growing up, navigating puberty, learning more about their identity and eventually understanding being nonbinary and asexual.

Most of the exploration and discovery happens in college or graduate school, including the sex scenes. Some conservatives have claimed the characters are underage in the scene, which isn’t true, and the scene is consensual and short.

All three books were put under review in Waukee and had been removed from library shelves in the meantime.

Keenan Crow, the director of policy and advocacy at One Iowa, an LGBTQ advocacy organization, explained why people focus on the scenes they do.

“They’re taking the bits that they know are going to provoke some sort of disgust reaction as soon as they are shown or read aloud. They’re completely decontextualizing all of that just so that they can activate some sort of disgust response in their audience,” they said. “And that is only effective if you take those bits in isolation. If you read the whole text, it doesn’t provoke the same kind of response.”

[inline-ad id=”0″]

How The Students Feel

Adrieanah Hamand, a senior at Northwest High School in Waukee, said books like these are often teens’ only source of information about safe sex and communication outside of the little bit they had in school.

“There are kids my age out having sex and practicing safe and unsafe sex and all that stuff,” Hamand said. “It’s not completely inappropriate for these books to be in our libraries.”

Brett Jenecke, another senior at Northwest High School in Waukee, said teens could be doing a lot worse than reading books and learning about themselves.

“At least in a book, it’s very unlikely to get that misinformation. But anyone can post anything on the internet,” Jenecke said. “As a member of the student body, I can say your kids know a lot more about this than you think they do.”

[inline-ad id=”1″]

He said having books such as these earlier in his life would have made a difference for him.

“I lived a lot of my childhood thinking I was different or abnormal in instances because all I ever watched growing up were straight couples, straight relationships, so I always felt like I was outcasted in some way,” he said.

Hamand agreed. In fact, she and Jenecke dated before they both learned more about LGBTQ identities.

In sixth grade, Hamand, who goes by she/they pronouns, said they were able to find, for the first time, media that represented how they felt.

“That was huge for me because I always knew there were some times, and I’m still figuring myself out, that I’m not always comfortable being called she,” Hamand said. “We realized through the media in sixth grade that we didn’t have to hide our identities and that it was okay.”

[inline-ad id=”6″]

But even if the books are ultimately removed from the library, it’s unlikely students will lose all access to representation, according to Colson Thayer, a senior at Northwest High School in Waukee.

“I don’t think that these parents are ever going to take away representation from queer people,” he said. “But kids will always have the internet. Kids will always be able to talk to other people. They’re always going to be able to go to a bookstore and find that book.”

Thayer said that’s how he’s found LGBTQ material, and that he never expected to find it in the high school library. Instead, he sought it out on his own and bought it himself.

He also has a problem with how much everyone focuses on sex when it comes to the LGBTQ community, and how people forget there’s more to being gay than sex.

“People don’t understand that there is a romantic side to it,” Thayer said. “There is just like a normal, everyday side to it, just like people are gay, but people automatically think it’s like a sexual thing.”

All three students said people should consider why they have problems with LGBTQ content, but not books with straight sex scenes, whether it’s fiction or the author’s experiences.

[inline-ad id=”5″]

Controversies Not New

Flagging books with LGBTQ content isn’t new. For years, lists of the top 10 most challenged books in schools have featured at least one LGBTQ title, according to the American Library Association.

In recent years there have been several LGBTQ books.

“There’s always this effect that when previously marginalized groups are more fully integrated into society, that a lot of these fears come up and in very predictable ways,” Crow said.

They said book challenges, particularly books by LGBTQ authors, is common, and part of an old strategy meant to shut down information about those marginalized groups.

[inline-ad id=”1″]

Jenecke and Hamand said they’ve been through their share of pointing and name-calling since they’ve come out, and this outrage is more annoying than anything.

“It’s just exhausting that now we’re having to go through a fight about books, which has been a fight that we’ve already won by getting them in our libraries in the first place,” Hamand said. “Taking away this media won’t force your kids to be straight. If they are LGBT, they’re just going to push you away the more that you try to push away their sexuality.”

by Nikoel Hytrek

Posted 11/12/21

[inline-ad id=”2″]

Politics

It’s official: Your boss has to give you time off to recover from childbirth or get an abortion

Originally published by The 19th In what could be a groundbreaking shift in American workplaces, most employees across the country will now have...

Trump says he’s pro-worker. His record says otherwise.

During his time on the campaign trail, Donald Trump has sought to refashion his record and image as being a pro-worker candidate—one that wants to...

Local News

No more Kum & Go? New owner Maverik of Utah retiring famous brand

Will Kum & Go have come and gone by next year? One new report claims that's the plan by the store's new owners. The Iowa-based convenience store...

Here’s a recap of the biggest headlines Iowa celebs made In 2023

For these famous Iowans, 2023 was a year of controversy, career highlights, and full-circle moments. Here’s how 2023 went for the following Iowans:...